By Ruth Anne Hammond

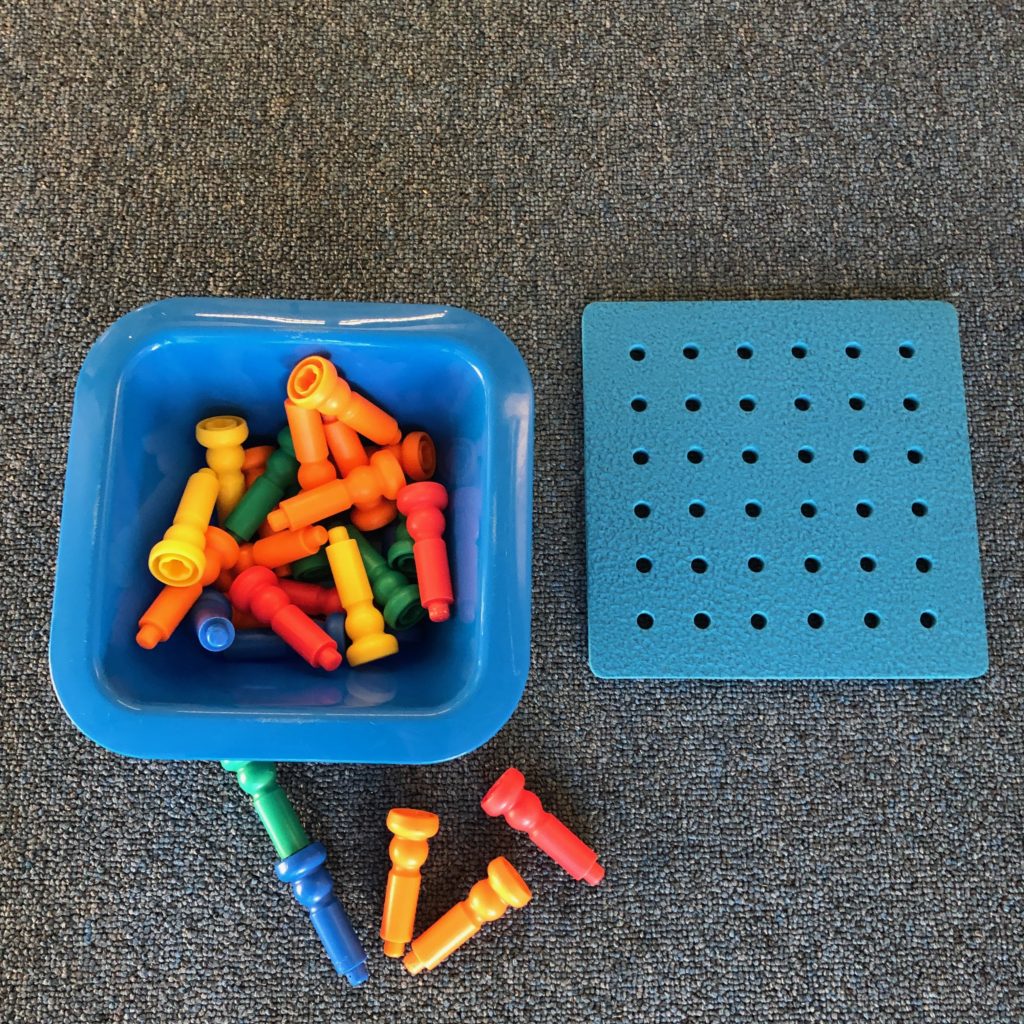

Picture this bowl of multicolored pegs and rubber peg board in my older toddler classroom setup. The children have not seen these objects before as far as I am aware. I know that they can be used to make a very lovely “birthday cake,” or if nested one in the other, to construct a very powerful something (a pole, a baseball bat, a rocket ship?). What possibilities do the children see? How long will it take them to figure out that the pegs are good for more than dumping and scattering? (A roomful of scattered pegs is NOT my favorite thing – they hurt if you accidentally step on them!) My heart is really in their independent discovery of the more complex uses, but to be honest, I secretly want to demonstrate. I know how much fun they are going to have once they know how to poke the small end into the larger end of the other peg, or push them into the peg board.. I’ve observed children discover this many times over the years. So why do I have this urge? For the same reason as most others – I’m a basically helpful person. (And I like to play, too.) Then why don’t I help? What holds me back?

As the Swiss researcher, Jean Piaget, wrote, “Whenever you teach a child something, you forever destroy her opportunity to discover it for herself.” Children’s joy in making a discovery is well worth the self-control it takes not to demonstrate the solution to a problem they are working on. It is tempting to want to jump in, but if you are constantly demonstrating, they don’t get the experience of inventing reality for themselves. Piaget coined the term ‘constructivism’ based on his observations of the way in which children build up (construct) their understanding of the world, through their own active explorations of the elements in their environment, starting first with their own movements, and face-to-face interactions with parents or other significant adults, and as they gain physical control of their hands, with objects.

To me, it is magic to sit quietly and watch a baby or toddler probing and testing for understanding. And when they catch my eye, wanting to see if I saw what they were doing, I can add the element of language without interrupting their train of thought. I let them know I appreciate their active intelligence just by saying, “Oh, the ball rolled a long way!” I don’t need to coax or test (“What color is the ball?”), I just need to share their joy of discovery with a few descriptive (not evaluative) words. [Stay tuned for more on evaluative words.]

Babies whose experiments are appreciated for the scientific method naturally employed become toddlers who are able to stay with an activity for long enough to truly educate themselves, and older children who have the expectation that if they keep at something, they are likely to succeed, or if not succeed, learn something useful for the next experiment or assignment. And you know what? When I have successfully stopped myself from inserting my ideas into their play, that “rocket ship” of pegs gives me a rush of pleasure (and pride) parallel to their burst of joy in their discovery. Try it yourself and see if it’s not worth the effort of holding back. Maybe you’ll become a constructivist, too.